Vernon Wells is someone that really needs no introduction, as his roles in movies like Mad Max and Commando define 80s action film villainy. I had the chance to interview him by phone in advance of the release of his film Tales from the Other Side and had a blast learning more about this hard-working actor.

You may notice how many times the word (laughs) appears. That’s no accident. Mr. Wells is one of the best-humored and genuinely funny people I’ve had the incredible opportunity to interview.

B&S About Movies: How did you go from working in a quarry to being an actor?

Vernon Wells: Well, I was a dumb ass (laughs). To be perfectly honest, I never wanted to be an actor. I was working in bands as a vocalist and following in the footsteps of my mother. Then I was in a car accident and I compressed three vertebrae in my back so I wasn’t able to do much. I was becoming very painful to be around so my manager took me around and got me work as an extra’s extra. Way back in the background.

I started getting work because I could ride horses and drive anything with wheels and shoot anything that’s a weapon. So I became the go-to boy for a while.

Then, George Miller’s girlfriend caught me in a stage play in Melbourne called Hosanna. It was written by Michel Tremblay, a French-Canadian writer, and about how Montreal wanted to secede from Canada and become a French-speaking autonomous area. I had one of the leads — it was a two-person play, so yeah it was a lead (laughs).

She spoke to George after seeing me, I spoke to George and the rest is history as they say.

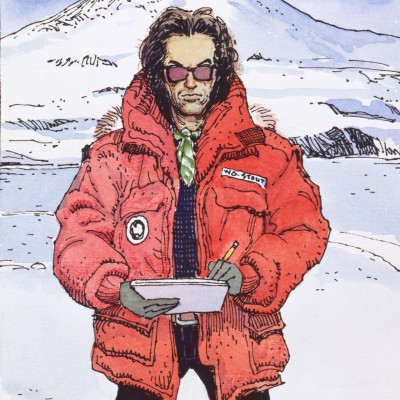

Vernon about to do something ill-advised.

B&S: What was it like to go from a background character to suddenly being part of Road Warrior, a movie that became famous worldwide?

Vernon: Terrifying. If I had it my way, I probably would have never done it. And I had never really done a film, so I had no idea. I thought that it would be fun but I had no idea what I was in for.

B&S: You did the stunt work too, right?

Vernon: I did a lot of the stunt work on it.

B&S: Was it as terrifying as it looks in the film?

Vernon: It was probably more terrifying (laughs). Because we were doing it! No, it was very safe. George is very critical of anything that looks like it won’t be safe or that people could get hurt. He will figure out ways of doing it so that you’re not going to get hurt but it’ll still look terrifying on screen. I have to give him that. He always makes sure the actors and crew are taken care of.

Because I don’t care who you are, you can’t 100% of the time be safe all of the time. Someone is occasionally going to get hurt. Thankfully, no one was seriously injured except for the stunt coordinator. I think he got the same thing I got when I was young, the accident that I had before I became an actor — a compression fracture.

All that wild stuff we filmed and the fact that just one person got hurt was amazing.

Then again, we could show you where we buried the people who didn’t make it, but of course, we don’t talk about this. (laughs)

B&S: How did you end up in Weird Science?

Vernon: Joe Silver the producer decided that he wanted me to reprise the role of Wez in a comedy and I didn’t want to because it was like, “This isn’t gonna work.” We had to change the look and costume because of copyright infringement. And then it turned out to be great.

B&S: In my small hometown, it was a battle to rent Commando at the video store. And you’re so incredible in that.

Vernon: I find it it’s incredibly enchanting that people actually think enough of what I do in a movie and tell me, “Oh, I dressed up as you for Halloween.”

I think that’s the pinnacle we all look for is that people get so involved and invested in the character that they see themselves as that character. And just to have that is the greatest accolade an actor can get. Way more than any bloody awards.

B&S: It’s because you took what could be a generic bad guy role and you made a meal out of it.

Vernon: I think it’s because I was doing it my way. I believe one of the comments from Arnold was, “Never give him a real knife.” He was a bit afraid about me actually cutting his throat!

I couldn’t see any other way of doing the character because Arnold is so big. And if I don’t act bigger than him, my character is going to look so weak.

“Let off some steam, Bennett!”

B&S: I’m sure you’ve heard that both Wez and Bennett are homosexual characters.

Vernon: Yeah, I love that. I was gay in Road Warrior according to half the world and I was gay in bloody Commando too! (laughs)

No, I don’t think Bennett was ever in love with Matrix. I think what he thought was that he was better than him And the only way he could prove that — the whole film was about how he set up everything he could set up — the point for him was who was the tougher man when the two of them finally faced off? Mano y mano, only one could walk away.

Why would I fight him if I was in love with him? I was pissed off. I wasn’t him. I wanted to be the big boy. I wanted to be the big kahuna.

B&S: People find subtext in things even if you didn’t even think of it when you were the one actually acting in the role. They insist that it has to be true.

Vernon: Yes! Everybody insists that the kid on the back of a bike in Road Warrior was my boyfriend. Actually, I rescued him from being killed and he was like my son!

People buy into a theory based on one scene without looking back on what happened before. When I got pissed off that he got the boomerang in his head, well…and he was my son and then he got killed. Why wouldn’t they take it the other way?

B&S: I saw Road Warrior perhaps way younger than I should have, at a drive-in, and that scene was the first thing I saw and I was shocked.

Vernon: (laughs) Well, here’s how I look at it. The point is that my job, as an actor, is to give you an hour and a half to two hours of total fantasy. I need to take you away from the everyday problems of the world and even yourself and what’s going on around you. My job is to put you somewhere that has nothing to do with that. I want to give you a respite. And that’s what I look at as my job…to help people forget.

B&S: The escapism has become so necessary today when so many bad things happen outside our doors now. Road Warrior is looking more real every day.

Vernon: if you look at Road Warrior now, you go, “What was George Miller on when he wrote this?” (laughs)

Because so much of what we live in now today, the world is getting that way. You may not have all of the weird cars, but you do have the weird dress and weird clothes and what’s happening right now, you look around and say, “What happened?”

B&S: I didn’t think the end of the world would be being quarantined in my house. You didn’t prepare me for that!

Vernon: What’s going to happen when gas gets to $10 a gallon? It’s gonna be mohawks and assless chaps from here to the ocean! (laughs) It’s $6.46 here in Los Angeles!

B&S: You’ve done so many memorable roles. Innerspace was a huge movie.

Vernon: Innerspace to me was funny because space was. To me it was funny. Interesting, because Spielberg loved the role I did in Road Warrior. And what he wanted was to create that character in his own way. But with Mr. Igoe, I couldn’t talk — I just had to be this entity, this thing and when you turned the corner and saw him, you just turned back.

It was actually a difficult part for me to play. I’m silent, I have on sunglasses and I had a fake arm. So it was like everything that I used to act was taken away and I was like, “Damn, what do I do?”

And I loved it. I thought that was such a cool movie. It was really cool to be able to put all those emotions on screen without talking.

And that was my introduction to Joe Dante! and I did three films with him. Love him!

B&S: You’re great in Looney Tunes: Back In Action as the Acme VP of Child Labor,

Vernon: That was so fun. That movie was never done as a comedy, it was done very straight. It was like another world! It was just so fun! I love all that kind of stuff. Like everybody was very strange, these major actors are being serious but saying these lines. He doesn’t play it for laughs which is why his movies are so funny.

I mean, only Joe could make that movie with the little guys — Gremlins! — and make it work. They’re so cute and then you get them wet and they become raving lunatics!

B&S: You’re in two different movies called Fortress. Which is better?

Vernon: The 1985 movie — that’s based on a true story and that’s why it’s so interesting. The kids were taken hostage and buried, then held for ransom. The kids didn’t escape and kill them, that’s made up for the film, but otherwise, that’s a true story.

I really enjoyed the other Fortress because they didn’t have a role for me. I auditioned and they liked me so much, they wrote Dabby Duck just for me. I’m 999 or 666 whichever way you look at me. I loved it and I had so much fun with the cast. We filmed it in Australia and I knew most of the crew.

B&S: You’ve been in a lot of cyberpunk films! What do you love about the genre?

Vernon: They don’t take themselves seriously. They do things that make you think, but they don’t take themselves seriously. They also often make you decide what is a good idea or a bad idea. And I like that attitude because it gives people a reason to want to go and see it so they can decide what they think on their own basis.

Vernon as Plughead from Circuitry Man.

B&S: You have so many different fandoms who know who you are. Some of them might only know you as Ransik from Power Rangers Time Force!

Vernon: It’s never little kids that come up to me at a convention that know that. It’s 25-year-old adults who are still mad that I killed the Red Ranger! (laughs)

Actually, I thought that series was really good because they really wrote good scripts. I’m very proud of it because they did a lot with my character. With Ranik, for the first time on that show, they did a backstory so you could see why he was the way that he was and maybe you understand him a little better. In other series, the villain is just the villain. He was once a doctor or scientist and not totally evil. I thought that was so interesting.

B&S: You also worked with Fred Olen Ray on Billy Frankenstein.

Vernon: I loved Billy Frankenstein and I loved Fred Olen Ray. It was such a fun movie. I had such fun with that character and that totally way out there — that scene where I don’t realize that I’m talking to the real Frankenstein! I loved it!

B&S: What’s the best role you’ve done?

Vernon: To answer that, I’d have to say there are probably five or six films that I’ve done. One was Beckett in King of the Ants. The role I have in it…they say no good deed goes unpunished and my character is a villain trying to be good and it ends up getting him killed!

There’s another one coming out where I play a priest and another where I’m a doctor who is trying to help a married couple dealing with cancer. There are a lot of really, really good films that I’m doing which has really good storylines and they have better storylines than a lot of the stuff I’ve done prior to that. Don’t get me wrong, I love everything I’ve done. But these movies are more adults now if you get what I’m saying.

Don’t get me wrong, I still like doing movies where I slam things around. But I love doing these movies where I am really getting into myself and my roles. I get to have a variety of now — fathers, grandfathers, not just the bad guys, though I still do that!

B&S: You’re so busy! Are you enjoying it?

Vernon: When I’m hired, I’m the happiest bloke in the world.

B&S: Tell us about Tales from the Other Side.

Vernon: It’s got some great stories that are all different and quite horrific. Each one gets more horrific! I’ve done two movies like this before and there was one where it was the devil coming to Earth and it was just him and me. I love that! I love anthologies because you get to tell a similar story three or four different ways and see how different directors and their actors handle that story.

B&S: So were you in a Fantasm movie? Or Felicity? I don’t want to embarrass you.

Vernon: (laughs) Don’t worry about it! When I was being an ass, my mother would threaten to tell my friends, “Vernon is doing porn now.” We all have something in our closets!

You can see Vernon Wells in Tales from the Other Side, a movie in which three kids want to have the most legendary Halloween night ever. It’s now available on DVD and on demand from Uncork’d Entertainment!

\

\

You must be logged in to post a comment.