Here’s the U.K. Section 3 “video nasty” in the man-against-the-wilderness genre that began with Sam Peckinpaw’s Straw Dogs (1971) from 20th Century Fox and solidified with John Boorman’s Deliverance (1972) from Warner Bros. Produced for a little over $2 million, Straw Dogs stumbled with $8 million in U.S. box office. Produced for $2 million, Deliverance raked-in over $46 million in U.S. box office: thus, we remember and credit Boorman’s work for kickstarting the genre — as well as the revenge-rape sub-genre.

The revenge-rape sub-genre quantified with Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left (1972), which was a sloppy n’ scuzzy, grindhouse remake of Ingmar Bergman’s tasteful-superior The Virgin Spring (1960). The sub-genre only got worse with the likes of the bogus, faux “sequels” in Roger Watkin’s Last House on a Dead End Street (1977) and Francesco Prosperi’s The Last House on the Beach (1978). Then there’s Charles Kaufman’s black comedic take on the genre — courtesy of the joint thespian tour de force by the actors behind Mother and her hicksploitation-bent sons Ike and Addley — with Mother’s Day (1980). Even Aldo Lado, he of the (brutal) Dario Argento rips Short Night of Glass Dolls (1971) and Who Saw Her Die? (1972), got on board the “Last House” caboose with Last Stop on the Night Train (1975), which — amid its Hallmark Releasing title myriads for drive-in and home video — was known as The New House on The Left, Second House on The Left, and Last House Part II.

While James Dickey’s screenplay was based on his novel Deliverance — which takes the Ingmar Bergman highroad — was graphic in nature, the violence was merely a delivery system of an underlying social statement about America’s class structure asking the questions: Who is stronger in a battle of wills between primitive man vs. civilized man. How deep into one’s base instincts will a civilized man delve for self-preservation?

So when you have a film produced for a couple million bucks pulling down mid-double digit millions at the box office, you know what that means: here comes the cash-in knockoffs.

All of the subsequent man-against-the-wilderness tales produced in the Deliverance/Straw Dogs backwash threw away plots (that were cookie cutter boiler plates, anyway), character development and underlying themes, and amped the violence — even more so in a post-John Carpenter Halloween world of the faux-Giallo variety. Macon County Line (1974), Death Weekend (1976), Jackson County Jail (1976), Rituals (1977), Just Before Dawn (1981), and Walter Hill’s Southern Comfort (1981) each own their debt to Boorman’s backwoods-terror vision. The home invasion and rape-revenge genre went off the graphic rails with the likes of Sergio Martino’s Torso (1973), only to get cheaper and shoddier with the likes of Linda Blair’s Grotesque (1988), then more “artful” with the likes of Gaspar Noe’s Irreversible (2002) and Takashi’s Ishii’s Freeze Me (2000). The most infamously scuzzy of the bunch is Meir Zarchi’s I Spit on Your Grave (1978). And the genre continues as streaming fodder with the classy Australian change-up, Rage (2021).

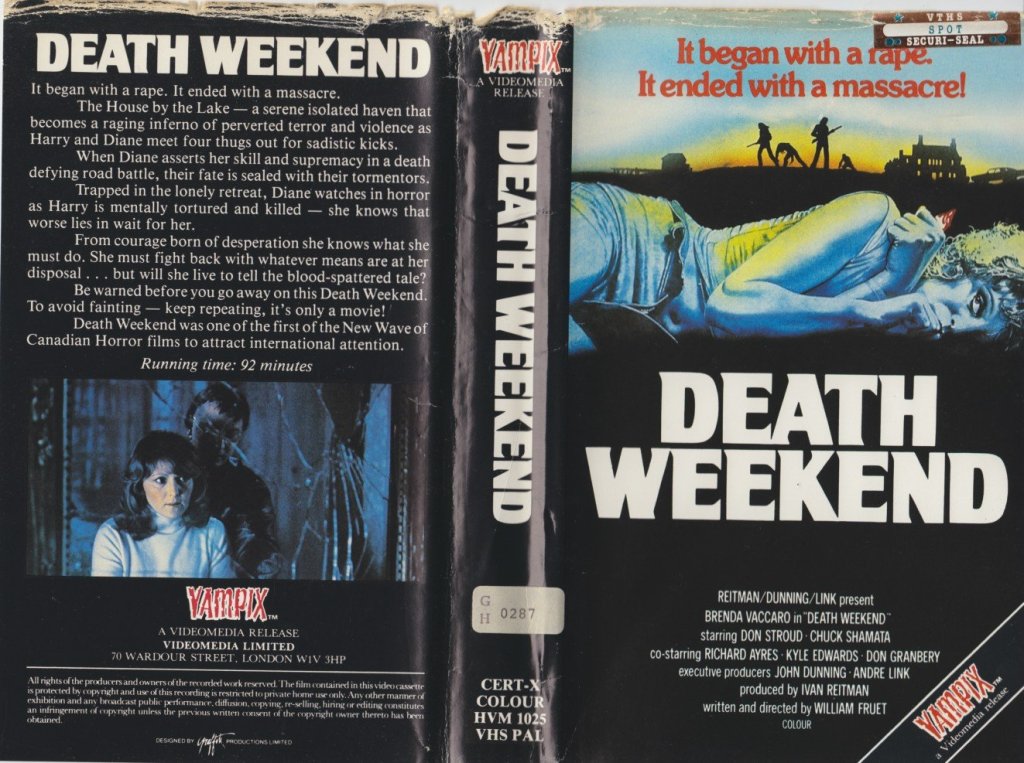

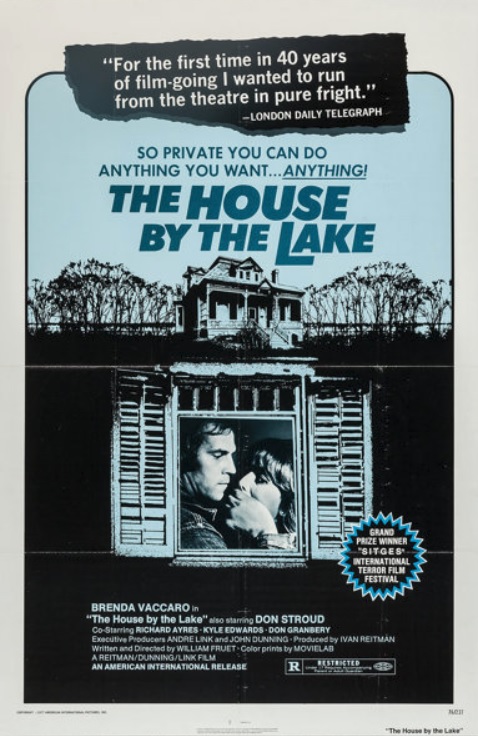

Released to Drive-Ins as The House by the Lake, and then bestowed the Death Weekend title for home video, this low-grade Canadian inversion of the genre produced for a half million dollars was written and directed by William Fruet for American-International Pictures. The film caused quite the stir as result of the intensity — more so that what we watched in Straw Dogs and Deliverance — for its drudgery in violence and rape for the sake of violence and rape. While Brenda Vaccaro and Don Stroud are stellar in their roles, the “message” was tossed out to tumble down the main road and leaves us with a movie that makes us wanting to take a shower after watching. It’s no wonder the VHS was seized and confiscated in the U.K. under “Section 3” of the Obscene Publications Act of 1959 during the “Video Nasty” panic of the ’80s.

The U.S. and English-Canada VHS released by Vestron as Death Weekend is sans three scenes: an additional shot of Don Stroud’s Lep on top of Brenda Vaccaro’s Diane as he attempts to rape her, a more graphic shot of Diane slashing Richard Ayers’s Runt’s throat, and a longer shot of Don Granberry’s Stanley burning to death. However, French Canadian and Spanish home video renters were allowed to watch those scenes, intact. Death Weekend has yet to receive a domestic U.S. DVD release; it was released in Sweden as an uncut DVD in 2017 by Studio S Entertainment; in 2019, Death Weekend was released on Blu-ray in Germany. Once offered as an a U.S. VOD stream by Amazon, the film is no longer available. Diabolic DVD has copies of the Swedish all-region Blu-ray, but are currently out-of-stock (keep checking back with them for re-stocking information).

Writer and director William Fruet is a name we speak of often amid the digitized pages of B&S About Movies, as we’ve enjoyed his oft-HBO-ran works Search and Destroy (1979), Funeral Home (1980), Spasms (1983), Bedroom Eyes (1984), Killer Party (1986), and his Alien-inspired AIDS cautionary tale Blue Monkey (1987). And we particular enjoyed his long-not-seen radio DJ drama that he wrote, but did not direct, Slipstream (1973).

Fruet revisited the ‘ol fish-out-of-water backwoods shenanigans (with a unique hick-impaled-by-TV antenna scene and an unstoppable Henry Silva thespin’ it up while doused in hot tar) with Baker County, U.S.A. That film’s script came courtesy of ‘80s slasher-scribe John Beaird, who penned the entertaining My Bloody Valentine and Happy Birthday to Me. Shot for $2 million by Fruet, affectionately referred to as the “Roger Corman of Canada,” Baker County, U.S.A is basically the canuxploitation-version of the later-shot Hunter’s Blood (1986), itself a retread of John Boorman’s 1972 hicksploitation trendsetter.

While Fruet already proved his skills as a director on his first feature film, Wedding in White (1972), a film starring Donald Pleasence and Carol Kane that he also wrote, he fell out of favor with the theatrical industry to find work in television. An opportunity to get back into theatrical film work came courtesy of Ivan Retiman (later the director of Meatballs (1979), Stripes (1981) and Ghostbusters (1984)) and Don Carmody, who successfully produced David Cronenberg’s Shivers (1975) through Cinepix Films. They wanted another horror film: Fruet gave them Death Weekend. When the film was acquired by A.I.P – American International Pictures for U.S. Drive-Ins, the distributor changed the title to the House by the Lake for an all-female revenge double-bill with Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left, which raked in the dough during its run.

Is there a statement here as to the way socially maladjusted men view women as “meat,” with Brenda Vacarro’s Diane dually serving as nothing more than an objectified outlet for Don Stroud (and his repulsive backwoods buddies) to channel his mental impotence-born violence (everything be “the bitches” fault), while her weekend-fling dentist playboy (who enjoys snapping pictures through two-way mirrors) sees women as disposable play toys? Is there a statement that, regardless of education and social standing, “men are men,” that is, pigs slopping in the same trough, when it comes down to gratifying their base desires?

No.

When Varcaro’s Diane, who accepts a “weekend at my lake house” invitation from a successful dental surgeon, are we supposed to look at her as an opportunistic “gold digger” that deserves the terror of torture and rape? When she takes the wheel of her weekend fling’s shiny Corvette and gets involved in a faux-drag-cum-road race and runs Lep (Stroud) off the road, does she deserve a comeuppance for not knowing her place?

No.

Sure, William Freut put everything together well enough, and Brenda Vaccaro and Don Stroud are, again, stellar, but personally, I can’t rank this alongside Sam Peckinpaw’s Straw Dogs and John Boorman’s Deliverance. There’s a reason why, beyond clever marketing, Freut’s home invasion-cum-rape-revenge was paired with Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left and it found itself on the U.K.’s video nasty list. Fruet’s work possesses none of the class of Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring; it’s pure Meir Zarchi’s I Spit on Your Grave (1978) and Jim Sotos The Last Victim (1975) objectifying sleaze of the exploitation variety.

But you may like it. And if it’s your jam, stream on, my retro-analog brother. As Shirley Doe has come off the top ropes and told us may times: “films are funny that way.”

About the Author: You can learn more about the writings of R.D Francis on Facebook. He also writes for B&S About Movies.