Two men wanted the rights to the James Bond novels: Harry Saltzman and Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli. Broccoli wanted to make the films more than Saltzman and while they couldn’t agree on a sale, they would agree to make the films together.

The problem? Many studios felt that the Bond books were too British and too sexual, but United Artists agreed to release their movie, giving it a low budget. As a result, Saltzman and Broccoli created two companies: rightsholding firm Danjaq and Eon Productions, which would actually produce the movies. Their partnership would last until 1975’s The Man With the Golden Gun.

Speaking of bad feelings, the pair wanted to make Thunderball the first Bond film. However, there was an ongoing legal issue between the writer of a screenplay for the film, Kevin McClory, and the book’s author Ian Fleming. Keep this in mind as our Bond Month continues, as while it’s a footnote now, it becomes a major issue later.

The team behind the film decided that Dr. No, the second Bond book, would be the first movie. It made sense — the space race was on.

But first, they needed a director. Several — Guy Green, Val Guest, Guy Hamilton and Ken Hughes — turned down the project before Terence Young came on board. The future director of Inchon and The Klansman realized that in order for the sex and violence of the film to be palatable to a mass audience — and pass the censors — a sense of humor was necessary.

United Artists only gave a million dollars to get the film made, which necessitated plenty of creativity to get all of the bases and special effects into the film.

While original writers Richard Maibaum and Wolf Mankowitz wrote a script that was nowhere near Ian Fleming’s novel — they made Dr. No a monkey — the second draft was better, especially when script doctors Johanna Harwood and thriller writer Berkely Mather entered the project.

So after all that — there was a very important question: who would be James Bond?

Cary Grant was the first choice, but he’d only commit to one movie. Richard Johnson — who would be in plenty of spy movies soon enough — was also considered, as was Parick McGoohan thanks to his performance as Danger Man. Other names bandied about were David Niven (he’d play Bond in 1967’s Casino Royale), Roger Moore (more on him all month long), Stanely Baker, Rex Harrison, James Mason, Steve Reeves and Richard Todd.

There was even a contest to find who Bond would be. A model named Peter Anthony won, but wasn’t up to the task.

Enter Sean Connery, who may have showed up rumpled and unshaved to his interview, but had the right attitude. Director Young would take it upon himself to make Connery into Bond, sending him to his tailor and hairdresser before giving him a crash course in style, manners and the high life.

The visual look of Bond — the stylized title opening, the gun barrel beginning — all start here. It’s a modest film with much bigger goals. This was world-building and sequel making before many even considered what that meant.

The team behind the film also realized that marketing was essential to the film’s success — particularly in America. By late 1961, United Artists sent a boxed set of the books to newspapers, as well as a book explaining the character and, perhaps most importantly, a glamour shot of first Bond girl Ursula Andress.

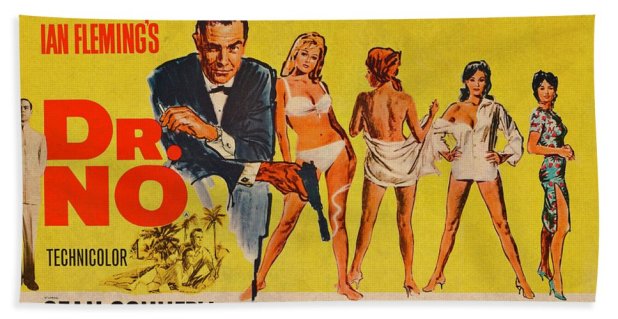

They also made merchandising deals with alcohol, tobacco, automobile and men’s fashion companies, using Fleming’s name and the success of the books to sell the character. And because sex sells, the posters featured Connery surrounded by gorgeous — and near-nude — women.

The results were pretty much an instant success. The films would become a series that nearly 25% of the world’s population has seen. The books became even bigger sellers. And the bikini — which Andress wore so famously — became the swimwear of choice for young women.

James Bond had arrived.

Bond has been called in to learn more about the disappearance of MI6 Jamaican station chief John Strangways and his assistant Mary Trueblood. Signal jamming of Cape Canaveral, the CIA (say hello to Jack Lord as Felix Leiter in the only time he’d play the role) and a bevy of assassins are soon involved.

The series stands out as something different right away, as after Bond escapes a tarantula death trap, he captures, interrogates and cold-bloodedly kills Dr. No’s associate Professor R.J. Dent (Anthony Dawson, who would return as Blofeld in From Russia With Love and Thunderball).

CIA agent Quarrel and Bond make it to the island of Dr. No, which is said to be guarded by a dragon — which is actually a flamethrowing tank. Bond meets Honey West (Andress) and after a battle that takes the life of Quarrel, he and West are taken to meet Dr. No.

As played by Joseph Wiseman (Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, Jaguar Lives!), Dr. Julius No is a Chinese-German supercriminal in the employ of SPECTRE (SPecial Executive for Counter-intelligence, Terrorism, Revenge, and Extortion). Due to radiation poisoning, he’s lost both his hands and has replaced them with robotic versions. He wants Bond to join SPECTRE and help him disrupt an American space launch, but you know exactly what happens next: Bond escapes the last death trap and kills just about everybody so that the free world can remain safe.

Dr. No also sets up Bond’s MI6 team of Miss Moneypenny and Q. Lois Maxwell would play the former role for the first fourteen movies, while Peter Burton would only play Q for this first movie.

Eunice Gayson (The Revenge of Frankenstein) plays Bond’s girlfriend Sylvia Trench, who was supposed to have a much larger role in the films. She was considered lucky by director Young, who cast her.

After seeing the movie for the first time, Ian Fleming summed it up quickly and candidly: “Dreadful. Simply dreadful.”

Luckily, the rest of the world did not agree.

You must be logged in to post a comment.