“The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun.”

— Solomon, Ecclesiastes 1:9

“Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.”

— French critic, journalist and novelist Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr

Whoa, ye Richard D. Zanuck and Jerry Bruckheimer: for both ye were begat by Solomon and Karr. For when one studio or producer puts a film into production, another will put their own Ecclesiastian version into production. And the Byrdian “turn, turn, turn” of those film sprockets were burnin’ the same ol’ sunny bulb down upon the same ol’ celluloid long before the dual gunfights at the O.K Corral with 1993’s Tombstone and 1994’s Wyatt Earp . . . and when Dreamsworks/Paramount and Touchstone/Buena Vista went to battle with their respective, 1998 God-brings-destruction-on-the-world romps Deep Impact (released in May) and Armageddon (July) (which continues to rain upon the Earth with the recent Greenland and its cheapjack clone Asteroid-a-Geddon) . . . and when 2013 was the year of our battle with the terrorist-attack-on-the-White House epics Olympus Has Fallen vs. White House Down . . . and, since we are in a sci-fi mood: the Lucasian vs. Glen Larceny slugfest of 1978, with the Battlestar Galactica set adrift in the Akkadese Maelstrom — that’s what you get for trying to make the Kessel Run, Glen, baby.

Karr was right: The more things change, the more they stay the same.

And the familiar tale of this production by veteran B-Movie and “poverty row” purveyor Monogram Pictures — The Asylum studios of the 1950s, if you will — starring Cameron Mitchell (who went from this to, ironically, the Battlestar Galactica-clone Space Mutiny), begins with producer George Pal.

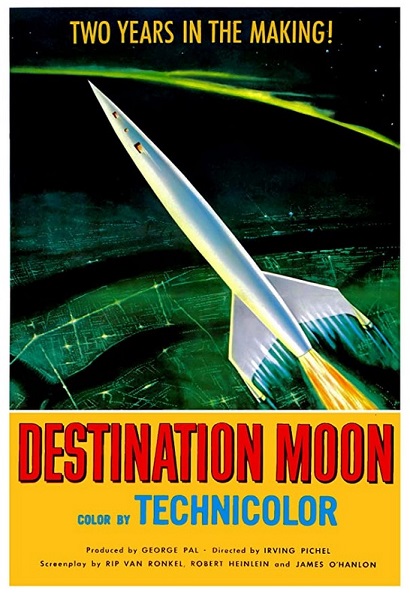

Pal purchased the rights to Robert Heinlein’s 1947 short story Rocket Ship Galileo (Heinlein’s work was also behind 1953’s Project Moonbase). With Heinlein serving as one of the film’s three screenwriters, it was turned into Destination Moon (1950). Pal’s first foray into sci-fi was the better remembered and more influential When World’s Collide (1951) (Paramount’s been trying to remake it for years), H.G Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1953), (remade, twice: Tom Cruise and The Asylum, natch), and the more scientifically accurate, but less remembered, Conquest of Space (1955) (that has no remake plans) (and you’re darn tootin’ Stanley Kubrick watched Conquest of Space; watch this You Tube comparison).

Well, studio chief Robert Lippert — whose Lippert Pictures would give us the failed, chauvinistic “matriarchy in space” romp that would be Project Moonbase (again, from a Heinlein book/script) — wasn’t letting George Pal one-up him. So Lippert rushed his own “first men on the moon” picture into production — and, as planned, beat Pal into theaters with Rocketship X-M (1950). While not as dry-to-boring as Destination Moon, Lippert’s copy is still talky and rife with scientific boondoggles in its tale of Lloyd Bridges (Oy! It’s Commander Cain from Mission Galactica: The Cylon Attack) in command of Earth’s first mission to the moon — that’s driven off course to Mars by an asteroid storm.

Imaginative, but ultimately undone by its cash-in cheapness to ripoff Rocketship X-M (which, again, hit the big screens first and ripped off Destination Moon), Monogram’s Flight to Mars concerns Mitchell’s philandering commander-in-charge of the Earth’s first (five-manned; four men and one woman) mission to Mars. Ol’ Cam’s the kind of leader that, sensing tension between the husband and wife engineering team on the trip, makes a command decision that flirting with the wife — in front of her man — is the right course of action. Batten down the hatches, this trip is gonna be a bumpy ride.

On Mars, our quintet meets the war-torn Martians forced to live in vast, underground cities (courtesy of pretty decent matte paintings; not Lucasian-stellar, but nice), who, regardless of their superior technology, need to steal our rocket design (because they’re tapped out of “Corium”), so as to launch an invasion to escape their dying world. And, in the grand tradition of ’50s sci-fi films — and the ’60s, such as the Italian romps 2+5 Mission Hydra and Mission Stardust — Earthmen and alien chicks (and vise versa) must have an interstellar romance. So, Marquerite Chapman’s Alita (her most notable roles were in 1952’s Bloodhounds of Broadway and, with Marilyn Monroe, in 1955’s The Seven Year Itch), a Martian babe who heads the resistance underground, betrays her people when she falls for Mitchell’s Col. Steve Abbott. No, wait. Col. Steve is hookin’ up with Carol the Engineer; Alita’s hookin’ up with Carol’s soon-to-be-ex (if Mitchell gets his wish), Dr. Jim Barker.

Okay . . . let’s put the flight recorder on hold for a moment, Flash. Let’s review the “romance,” i.e., the philandering, and cosmic chauvinism.

Flight to Mars is the type of film where:

- Although a woman is intelligent enough to engineer a rocket and is the only one qualified to monitor its systems, when she gets to Mars, her first question to her Martian hosts is “Where’s the kitchen?” and express amazement that “Mars is a woman’s paradise” because all food preparation is done in a lab and dish washing is done by machine. “Mars, I love you,” says the female rocket scientist.

- Women are still objects of another crew member’s ogling and flirting, even though her husband/fiancée is also on board — and the woman reciprocates the pass because, even though the man is a pig, the woman is still a Jezebel that tempted the man to be a pig in the first place.

- A woman, while sorta-kinda of cheating on her husband in the lab with another crew member, gets jealous when her husband tries to hook up with a Martian chick because, women are Rachel Green-styled emotional basketcases who love to instigate love triangles, only to leave tables and rooms in a huff.

- Oh, and when women board a rocket, no flight suit or pressure suit is required: but they do need to wear a below-the-knee skirt, stockings, and heels. Just strap in, forget the helmet, freshen the lipstick, and hit ignition. Per aspera ad astra, sweet cheeks; for a kitchen awaits you on the angry red planet.

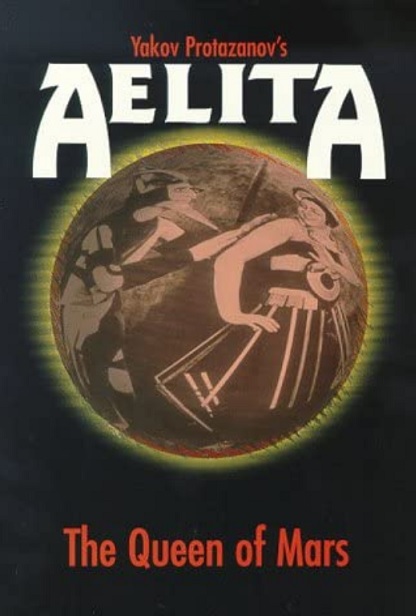

Now, if you’re keeping track of your classic sci-fi: Martian women falling for Earthmen dates back to Alexei Tolystoy’s novel Aelita (Ah, okay, you removed the “e,” eh, Monogram?), which was silent-film adapted in 1924 by Yakov Protazanov as Aelita, Queen of Mars (one the earliest, full-length science fiction films regarding space travel), and concerns a totalitarian Mars overthrown by Queen Aelita and her Earth-man lover. In fact, the true source material behind Monogram’s space opera isn’t Rocketship X-M or Destination Moon: the source is the English-dubbed and edited version known as Aelita: Revolt of the Robots, released in 1929. Yes, the ill-remembered Flight to Mars is a remake . . . and a ripoff . . . in one fell spin of the celluloid sprocket. And you thought The Asylum invented the Glen Larceny business model, first, huh?

So, that’s three films Monogram’s clipped . . . and 2+5 Mission Hydra and Mission Stardust, in turn, clipped them. And the women — both terrestrial and celestial — and as in The Angry Red Planet (the ultimate in creepy astronaut-leering adventure), Gog, King Dinosaur, and the aforementioned Project Moonbase — are Bechdel-tested into interstellar dust in all of them. At least Mission Mars (released in the Year of our Kubrick, 1968) had the good sense to keep the woe-is-me women on Earth and give us the good ol’ (goofy) non-human monster-aliens. (Dishwashers on Mars? Women are free from cooking and cleaning? Obviously, screenwriter Arthur Strawn — of 1935’s The Black Room starring Boris Karloff — from had matriarchal issues.)

We’re not in a spec of original space anymore, Toto! Wait, Auntie Em? This all looks familiar . . . beyond the script . . . wait, it is the same!

As with Roger Corman laying down the big bucks to produce his Star Wars cash-in, Battle Beyond the Stars, then reusing that film’s sets (and footage) in Forbidden World*, Galaxy of Terror*, and Space Raiders (yes, and Android and Star Slammer!), Robert L. Lippert maximized his bucks; he rented out the sets, props, and sound effects from Rocketship X-M to Monogram. While it’s not a “green movie” as Cat-Women of the Moon, these Mars proceedings are definitely a hue of bluish-green (or yellowish green?). Sure, Monogram redressed things a bit to make us think it’s all different, but it’s not. Well, outside of the fact that Rocketship X-M was shot in black-and-white and starts off to the moon and ends up on Mars, while Flight to Mars is shot in color and went to Mars as planned.

The UHF-TV highlights of director Lesley Selander’s 40-year and 145-plus film career include — for you ol’ black-and-white horror hounds, The Vampire’s Ghost (1945), War Paint (1955; with Robert “Unsolved Mysteries” Stack), and Fort Yuma (1955; with Peter “Mission: Impossible” Graves”; he went to the Red Planet himself with 1952’s Red Planet Mars).

You can watch Flight to Mars on YouTube while your woman heads to the kitchen to make you a sandwich. And be sure to pour a Dr. Pepper, babe.

Be sure to look for my upcoming “Space Week” reviews of Mission Galactica: The Cylon Attack, 2+5 Mission Hydra, Mission Stardust, and Mission Mars this week.

*There’s new reviews for both Galaxy of Terror and Forbidden World as part of our “April Moviethon 2” blowout, as day “Day 5” celebrates Roger Corman’s Birthday.

About the Author: You can learn more about the writings of R.D Francis on Facebook. He also writes for B&S About Movies.

You forgot ANDROID (which also borrows that space battle footage from BEYOND THE STARS), if only three films reused BEYOND STAR’s footage that would have been a waste in Roger’s book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Erich,

Many thanks for the loyalty towards the hard work on this site: you not only visit frequently to suss out films to watch: you leave positive, uplifting comments.

Forgive this comment slipping by me and not acknowledging you, sooner. You’re absolutely right: I did forget ANDROID (ugh) amid all of Roger’s post-BBTS-verse flicks. And yes, it’s true: I think Roger has a unwritten rule (probably written into contracts!) that footage/sets from a director’s film must be re-used X-amount of times!

I think Roger’s mindset is that normal movie goers/renters (meaning not me or you!) may watch just ONE of his post-Star Wars droppings — and not ALL of them, thus, the normal person doesn’t catch the recycling. In fact — and I am talking off the top of my head (too lazy to look back at reviews) — speaking of sets, props and stock from the BBTS-verse: I forgot to mention Fred Olen Ray’s STAR SLAMMER as another one of those “familiar” films. As you know: Ray has worked for Roger, so there you go.

LIFEPOD from 1981 with Joe Penny? That’s by Gold Key Entertainment: they produced a flurry of several low-budget “Star Wars” flicks that utilized Roger’s recycling business model. So did EGM Film International with CONVICT 762 — and their own gaggle of late ’90s ALIEN knockoffs (four or five films, I believe). Again, only a dork like me watches ALL of these loosely connected films and notices these things!

As, always: thanks for the positive vibes!

LikeLike