27. TRANCING AND HYPNOTISM: Gold watches ain’t just for retirement.

I’ve been obsessed with this movie for years.

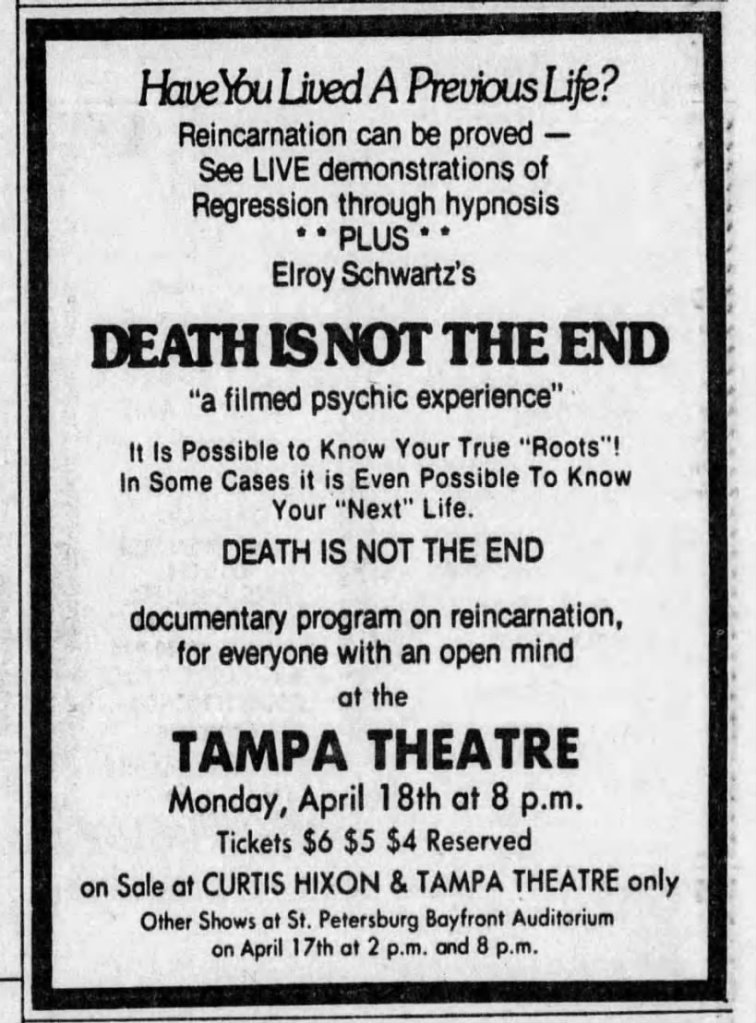

My Drive-In Asylum co-host Bill Van Ryn shared an ad for a movie that I’d never heard of on his Groovy Doom Facebook page, and it immediately piqued my curiosity. What could Death Is Not the End be?

Kinorium says, “The mystery of life eternal is discussed by a number of purported experts in various fields of metaphysical research, as well as individuals who assert that they’ve lived before.”

The AFI Catalog goes a bit deeper, telling us “Reporter Wanda Sue Parrott and an African American laborer named Jarrett X are put into deep hypnotic trances as part of a psychic experiment in past-lives therapy.”

It played at least a few times, if ads are to be believed. The Phoenix, AZ, premiere was on December 8, 1975 — the ad featured in this article — and it also played a year later in Los Angeles on April 11, 1976.

The July 25, 1974 Hollywood Reporter claimed that the film, then known as 75 IT, would premiere at the Atlanta International Film Festival in Georgia on August 16, 1976. Dona Productions took over distribution in 1976, and the film’s title was changed to ‘Death Is Not the End’, a title that hints at the film’s themes of reincarnation and life after death.

Anyways, these are a lot of facts, but there was no chance I was ever going to see this movie.

Or was I?

Imagine my surprise to open my email and see this:

Hi Sam,

We were given a big binder of family stories for Christmas, and in it was a DVD of 75 IT. We already had one, but it got me and my husband googling the movie and we found your blog.

I watched it years ago but am not sure I ever got to the end as it was pretty bad. I did enjoy the brief shots of my husband as a child at the very beginning.

I’m not sure who has the rights to it now. Wanda used to stay in touch with Ron Libert but I think they fell out over the publishing of her novel.

Are you still looking to watch it?

It took about six months to arrive. And you know how I work. When I get something I’ve been waiting to see, I tend to sit on it. Like gift cards, I like the idea of having something to look forward to. In this case, the anticipation of finally watching this rare and obscure film was too exciting to rush.

But today would be the day that I would watch this.

75 IT or Death Is Not the End was the work of Elroy Schwartz. The brother of Sherwood Schwartz, he and Austin Kalish wrote the original pilot for Gilligan’s Island, which went unaired until TBS showed it in 1992. He would continue to be a writer on the show along with his brother, Al.

In 2000, the Los Angeles Times reported that Schwartz and Kalish were suing Sherwood, saying, “They charge that the older sibling has been cheating them out of Gilligan’s Island credits and royalties for decades. The dispute apparently began in 1963, when Elroy and Kalish say they wrote most of the pilot show. Sherwood was the producer and, as a favor, they honored his request and listed his name as a co-writer on the script, the suit says. Ever since, they charge, Sherwood has tricked them out of their share of royalties and has controlled the rights to the show, which has made him as rich as, say, Thurston Howell III.”

They’re not exaggerating. In Kalish’s obituary in The Hollywood Reporter, it’s reported that “Years after the show ended, Kalish said documents were uncovered that indicated he should have been entitled to one-quarter ownership of the series, worth about $10 million, but he received nothing.”

In addition to being a writer, Schwartz was a licensed hypnotherapist specializing in past-life regressions. He described this movie as such: “There wasn’t any established script. The movie is a ‘happening’ — a spontaneous filming of a hypnotic regression into reincarnation, and ‘procarnation’ — a look into the subject’s next life.”

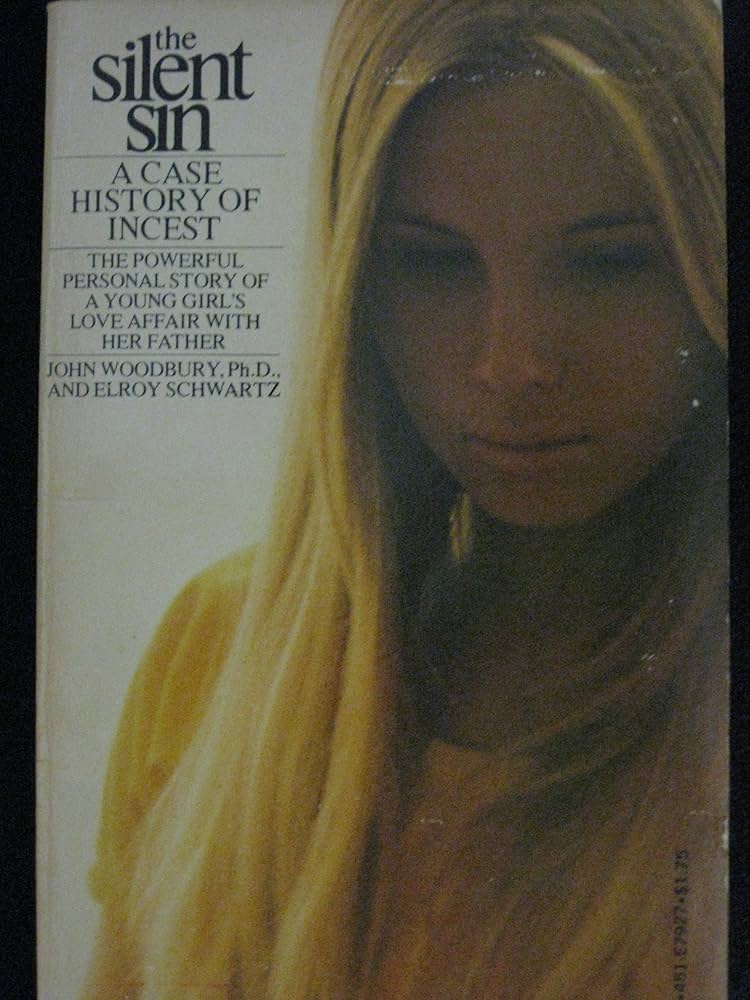

According to the article (The Tampa Times from April 4, 1977) posted above, “Elroy Schwartz, stocky, cordial, gregarious, doesn’t look like a Svengali, but, he says, he’s “a hell of a hypnotist.” Schwartz is in town from Los Angeles, where he’s a full-time writer and producer (he’s written for such TV shows as I Love Lucy, Gilligan’s Island and Movie of the Week and a sometime hypnotist who’s delved into uncharted areas of the mind. From these explorations have come both a book, The Silent Sin, and a movie, Death Is Not The End, scheduled for showing Monday night at the Tampa Theatre. His book, written six years ago, deals with a hypnosis subject whom he “regressed,” or took backward in time, over a period of several months, eliciting from her unconscious several past lives she felt she had lived in various reincarnations. In one reincarnation, the subject went through a reenactment of labor pains. For Schwartz, “It triggered something in my mind.” He thought, “If we can go backward in time, why can’t we go forward?” He tucked the thought away for a while, but some time later met Wanda Sue Parrot, a newswoman with the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, and “got good vibes from her.” They started work on regressing, and when he felt she was really in touch with her subconscious, Schwartz asked her to go forward in time to her next life.

He was in for a shock. Wanda was “reborn” as a mutant inhabitant of a world recovering from the near-annihilation of an accidental atomic detonation from China. What had been the United States was now “America’s Islands,” fragmented, with whole sections gone from the map. She lived in “Utah County” in the year 75 I.T., which, the hypnotist found, meant International Time, a time system set up by the “World Tribunal,” which governed what was left of Earth.

From the concept of this horror story emerged the movie, which was filmed live as Schwartz repeatedly put his subject into a trance state under the supervision of a medical doctor.

“It’s not edited except for time,” Schwartz said. “Producers have told me it’s not technically a movie, but it has a tremendous impact. Wherever it’s shown, people thank me. They want to see it again.” For himself, Schwartz “knows what we have is real. Maybe this is a warning; maybe we can stop history if we stop and think what we’re doing.” For now, he’s trying to find practical and creative ways to utilize his gift.”

So let’s get to the movie.

It’s wild: this is relatively low quality, but when you have what may be one of the few copies of a movie in the entire world, you don’t complain.

This film is relatively simple. Schwartz sits in a chair, a shirt unbuttoned to reveal a bare chest, speaking with Wanda Sue Parrot, who wrote for the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner and Chicago Tribune. As Schwartz hypnotizes her, she quickly remembers several of her past lives, including being a woman named Akina in an early civilization. Often, she is unable to communicate with Schwartz because there is no translation for her words or for how she sees things.

She starts as a single-cell organism, then gets brothers and sisters as a cavewoman, as Schwartz tries to get her to speak the language she used. The language can’t be identified as a modern language; it’s very rudimentary. It sounds Native American, which makes sense, as Parrot has Chickasaw and Cherokee ancestry in her family tree. She also wrote under the Native American byline Prairie Flower.

Schwartz then hands her the paper and a marker so she can write. Even though she’s a writer by trade, she struggles with the marker, biting down on a pencil as she creates a triangle. Synth music bubbles as she continues her drawing. In her language, she tells him what the drawing is. Then she says it’s a drawing of creation and how it came to our world. She says there are two sides of God, symbolized by two fish. She refuses to take the pencil out of her mouth so that Schwartz can understand her. He then puts her to sleep so he can get the pencil back, and asks her to wake up; he will be her god Ika. He will talk to her and she will understand him.

“You have been a good person, Akina. You may speak to your god.” Schwartz says. She laughs and says that Ika is invisible. He replies by walking out and coming back, saying that he’s Iko. She holds his hands and smiles, studying his watch, which she smells and tries to bite. She’s also interested in his many rings. “Ahh e tu ah,” she replied. Then says, “Snake.”

He puts her back to sleep.

Akina dies when she goes to see the blue people — is this Yor Hunter from the Future? — and she is crushed. She dies far below her people. Schwartz then counts to three and tells her to feel the pain of Akina as she dies on a bed of stones. Wanda begins to move around in pain, just as she’s told to go to sleep.

What about the blue people? Akina describes the geography of the world she lived in. The blue people raised cattle, sheep, and a bird. Their skin is as dark as ashes, but not black like ashes. A deep color blue like the sky. They were being extincted, and their women were unable to reproduce, having only one child each. Any children they had moved into new territories across the ocean, but their color changed to dark, but not blue, except in cases of…she doesn’t know the word. They had blue black skin, brown black skin. Then she discusses other people, like the Unix, who were the work animals.

Schwartz then tries to learn how the electron that she once was became the identity of a new person and how the soul moves through different bodies through time. We hear her be born and make very realistic noises as if she were a crying infant. He then takes her to the 1600s, where she is a French man. Wanda only speaks English and Spanish, not French, so when she starts to say things in French, it’s surprising.

The film cuts to a couch, where Schwartz meets Jarrett X, a black man wearing a dress shirt covered in dots and white flowers. He quickly is able to get Jarrett to go into a hypnotic state and remember being named Jacob Elliot Nash. After the Civil War, he worked on a farm for Master Hearst, a white man he disliked, who often beat him with whatever he could find. Schwartz tries to take on the voice of Jarrett’s master, yelling at him before learning that the young slave stayed behind on the plantation, bound by the fact that his mother would not leave.

This gets pretty harrowing, as Jarrett is asked to sing at one point and says that he refuses to sing as he no longer believes in God, as what God would allow so much suffering? Schwartz counts to three, snaps his fingers and reminds Jacob of when he was a child and did sing. He then relates a few bars of “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child.”

Then, the worst memory comes when Jarrett remembers the owner’s son stabbing him with a pitchfork, ending his life. This gets even harder to watch, as we learn that in the past, Jarrett was accused of fooling around with a white woman, which earned him his death. As Schwartz snaps his finger and wakes him up, he quickly seems like a totally different person.

Schwartz relates to Dr. Kent Dallt, Professor of Psychology at UCLA, how he wrote his book on hypnotherapy and reincarnation. As they sit in a field, they discuss how no one seems to believe in previous or future lives. Schwartz relates that even if he had proof that someone was actually alive —a newspaper article or a tombstone —no one would believe it. Skeptics never open their minds to these things.

Dallt brings up From India to the Planet Mars by Theodore Flournoy and Sonu Shamdasani. The book explores Catherine Müller, also known as the medium Hélène Smith, “who claimed to be the reincarnation of Marie Antoinette, of a Hindu princess from fifteenth-century India, and of a regular visitor to Mars, whose landscapes she painted and whose language she appeared to speak fluently.”

Death Is Not the End moves on to the procarnation exercises, which move Wanda to her next life as a blind mutant newly born in Cold Springs, Utah. Seventy-five years after a nuclear accident, which gives this film the name 75 IT, the United States has been divided into the American and Barbara Islands, which are ruled by the World Tribunal of Africa. As America has been decimated by this nuclear event, its people aren’t allowed to celebrate any religion, experiment with any science or even marry one another.

This is all supposed to be happening in the year 2100 or so, Schwartz thinks. All Wanda can say is that it’s the year 75 IT when Wanda’s mutant future form is twenty. She claims that her father was from Philadelphia. Elroy pushes her for more information on the accident, to which she can only reply, “Horrible. Horrible.” He keeps asking, and she tells them that people burned, their skin came off their bodies, their eyeballs fell out, and they still didn’t die.

No one knows why or how the accident happened, which doesn’t help us much. It wasn’t a war, she knows that much, and that it happened in China. Schwartz goes through several cities and asks if they are still around. Miami and Florida have sunken beneath the waves, but Omaha and St. Louis are safe. Most of the towns he throws out, she can’t remember, although she has heard of Birmingham. England is underwater with piranhas, she says, at one point.

The world is governed by the World Tribunal, which has representatives of every nation on Earth. Elroy then asks if she will always be in Cold Springs, but she will go to the University of Heidelberg when she’s 25. Oh yeah — Phoenix is a port now, too.

Throughout the interview, Wanda seems almost upset and struggles to explain herself. Schwartz even chuckles a few times. This makes me drift and see the room he has set up, which is very 1970s, with green shag carpeting, tons of plants, and comfy couches with afghans. It isn’t a place you’d discuss the end of the world.

She claims Kennedy would win the 1980 election, and Elroy quickly moves on. She then took up a lover, Joseph Martin, her lover from Belgium. He taught her how to see, which landed him in jail for treason. While she was blind, she was taught to see with the center of her brain or her third eye. Joseph showed her how to use transmission to see and how to use telepathy to see through his eyes.

There’s a wild moment here where the mutant wakes up in Wanda’s body and can see. She looks like she’s freaking out and then seems elated that she can see. It’s hard to tell if she’s sending messages back in time or speaking through this body. This moves her to tears.

The mutant dies in the year 106 IT. She goes home to Cold Springs to have her baby, the child of a criminal. She goes up the mountain and doesn’t come back. The baby is born. Schwartz wakes her up with a smile.

The end credits claim that the year IT is 2012. It also says that “Two months after the final edit of this film, Dr. Dallet, finding the film personally distubring, shared the Procarnation description of “the accident” with colleagues at the University’s Astronomy and Science departments. Their “concensus of opinion” theory was that “the accident” was probably a Pole Shift — cause by a weight imbalance at the poles due to a melting of the polar ice caps.”

There’s a producer’s note — which makes me wonder if this was planned to be released in 2005, before the 2012 event and in a time when polar shift theory was at its height — that says “In the thirty years since this documentary was filmed, much of the polar ice has melted — and continues to melt at an increasing rate. Thirty years ago, Earth scientists considered the melting of the polar ice as improbable and without precedent.

Death Is Not the End doesn’t feel fake. It feels like people are being captured in moments of hypnosis. Whether they’re guided to feel this way or they’re really sharing moments of their past and future is up to you, the viewer. It feels way too raw to be either improv or scripted.

I can’t even tell you how overjoyed I am to get this movie, and I am beyond thankful that it was sent to me. I wish it had a bigger potential audience than just movie nerds like me, as I can’t even see this being something a boutique label would release. But in a world where we can find everything within seconds online, the fact that some films remain hard to find — and therefore occult — is something that keeps me alive.

As bas as the world seems like it can be, we also live somewhere that the real creator of Gilligan’s Island can make an unseen movie about past and future lives, as well as an end of the world that never came.

Notes on the people who made this:

Richard Michaels directed the film and began his career as a summer assistant to legendary New York sportscaster Marty Glickman before becoming a script supervisor. He also directed episodes of Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and The Odd Couple, and produced Bewitched, a show he would direct for 55 episodes.

That show would change his life, as he and star Elizabeth Montgomery fell in love during the show’s eighth year, breaking up her marriage to William Asher and his to Kristina Hansen. They were together for two and a half years.

The rest of his career was spent in TV, mostly directing TV movies such as The Plutonium Incident and Scared Straight! Another Story, Heart of a Champion: The Ray Mancini Story, Leona Helmsley: The Queen of Mean and many more.

The music comes from Mort Garson, who wrote the song “Our Day Will Come,” which is on the soundtrack of Grease 2, More American Graffiti, Under the Boardwalk, Shag, Buster, She’s Out of Control, Love Field, The Story of Marie and Julien, You Should Have Left and Role Play. He was part of The Zodiac’s Cosmic Sounds, a 1967 concept album released by Elektra Records that had early use of the Moog synthesizer by Paul Beaver (“a Scientologist, a right-wing Republican, unmarried and a bisexual proponent of sexual liberation” who helped build Keith Emerson’s custom polyphonic Moog modular synthesizer, did the sound effects for The Magnetic Monster and composed the score for The Final Programme) with music written by Garson, words by Jacques Wilson and narration by folk musician and Fireside Theater producer Cyrus Faryar, all with instruments played by members of the Wrecking Crew studio collective, such as Emil Richards, Carol Kaye, Hal Blaine, Bud Shank and Mike Melvoin.

Garson was an early adopter of Moog, which makes me like him even if he wrote the theme song for Dondi. He also wrote the song “Beware! The Blob!” for the Larry Hagman-directed sequel and scored René Cardona Jr.’s Treasure of the Amazon, Paul Leder’s Vultures and Juan López Moctezuma’s To Kill a Stranger.

Plus, his song as The Zodiac, “Taurus – The Voluptuary,” also shows up in several gay adult films of the early 70s, including the Satanic-themed Born to Raise Hell, which also uses his songs “Black Mass,” “The Ride of Aida (Voodoo),” “Incubus” and “Solomon’s Rising.”

Garson was also Lucifer, the electronic artist who released Black Mass — also called Black Mass Lucifer — that AllMusic reviewer Paul Simpson says is “a soundtrack-like set of haunting Moog-based pieces which interpret various supernatural and demonic themes.”

Cinematographer Alan Stensvold also shot Bigfoot and Wildboy for The Astral Factor, Dimension 5, Cyborg 2087, Thunder Road, and the TV show Dusty’s Trail, where he had to have met Elroy Schwartz, who created the show with his brother Sherwood.

This movie was edited by Joan and Larry Heath. While Joan has no other credits, Larry has an extensive portfolio of work on TV, including 106 episodes of Rhoda, 46 of Simon & Simon, the film Billy Jack and episodes of Gilligan’s Island and Dusty’s Trail, where he also met Schwartz.

Notes on the production and distribution companies:

Schwartz’s Writer’s First only lists this movie and episodes of the show Dusty’s Trail as released productions.

Dona Productions seems made just to distribute this film,

Libert Films International was seemingly was a tax shelter used to distribute films like Rum Runners, Angela, Encounter with the Unknown, The Great Masquerade, My Brother Has Bad Dreams, Mario Bava’s Roy Colt & Winchester Jack, The Devil With Seven Faces, Never Too Young to Rock, Willy & Scratch, Charlie Rich: The Silver Fox in Concert, Beyond Belief and Stevie, Samson and Delilah. Ron Libert was the CEO of this company and Apollo Productions and was part of American Pictures Corporation, along with Robert J. Emery, who directed the Claudia Jennings-starring Willy & Scratch.

Cougar Pictures, which picked this up in 1977. also distributed The Flesh of the Orchid, Starbird and Sweet William, Scream, Evelyn, Scream! and another Libert pick-up, Beyond Belief.

You must be logged in to post a comment.