ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Jennifer Upton is an American (non-werewolf) writer/editor in London. She currently works as a freelance ghostwriter of personal memoirs and writes for several blogs on topics as diverse as film history, punk rock, women’s issues, and international politics. For links to her work, please visit https://www.jennuptonwriter.com or send her a Tweet @Jennxldn

The Japanese title of The Boy and The Heron translates to “How Do You Live?” The title of one of Miyazaki’s favorite books, although this film has nothing to do with that story.

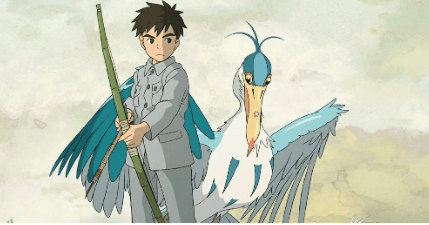

After his mother passes away in a fire during WW2, 12-year-old Mahito finds it difficult to adjust to life in a new location following his father’s re-marriage. After he is bullied in school, he self-harms to avoid going to class.

Mahito is visited by a talking heron who tells him his mother is still alive. He takes Mahito to an abandoned tower which serves as the portal to another realm. There, Mahito searches for his mother and meets all manner of mystical characters including a younger version of his mother.

The Boy and The Heron is Hayao Miyazaki’s most personal and abstract film to date. He made it for his grandson. It’s about the old and the young and loss and acceptance.

It feels like classic Miyazaki with a bit of David Lynch thrown into the mix. Visually, there’s so much detail, even in the quieter moments where nothing is happening, that it’s a film that will take most people more than viewing to absorb and unpack the meaning of everything on screen.

The possible interpretations are limitless. Is this a warning about perceived power in alternate realities i.e. the internet? Is it showing us the human side of militaristic societies like the ones that sprung up in WW2? Is it a Buddhist parable involving the realms of the gods (deva), the demi-gods (asura), humans (manuṣa), animals (tiryak), hungry ghosts (preta) and hell denizens (naraka)? I honestly don’t know. And I like it that way.

I’m fairly certain the granduncle, who lives in isolation with his pencil is Miyazaki. A man who neglected reality in favor of the worlds he created. It’s well-known that following the success of Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, Miyazaki threw himself into his work so much so that he neglected his wife and son Goro, with whom he has a strained relationship to this day. There’s also a lot of Miyzaki in Mahito, who grew up during and after WW2.

At one point, the grand uncle in the other realm taps 13 building blocks with his pencil and indicates a desire for a successor to all he has created. I’ve heard it suggested that the number 13 represents Miyazaki’s films, but this theory holds no water. There are only currently 12 films if you count the feature length works and if you count the shorts directed for exclusive screenings at the Ghibli Museum in Mitaka Japan, there are substantially more than 13. I saw the short, titled Mei and the Kitten Bus at the museum (the official sequel to My Neighbour Totoro) and it was delightful, even if there were no English subtitles. Totoro’s first appearance in a crowd of creatures carrying his umbrella solicited substantial “ooohs” and “ahhhs” from the audience, owing to how beloved this character is in Japan.

Whether Miyazaki-sensei makes another short or feature, it seems likely that The Boy and The Heron will be studied by future film scholars as one of his most important films. It’s rare that an aging director produces something this interesting.

For example: In the other realm, there parakeets. These birds are fascist militaristic, but they also love their families. Notice, in the adorable image below, the parakeets cuddling their unborn young? Clearly, the parakeets aren’t really the “bad guys.” They’re just like humans. They have merely fallen prey to the flock mentality and follow their king – who resembles Mussolini- blindly. Once the flock crosses over into “reality” they are rendered harmless.

Will it be his last? Time will tell. He’s “retired” several times before, but it seems as if creating the worlds in his mind is what keeps him going. Just like Granduncle.

The film ends with a new beginning. Mahito is free to create his own stories. There is no “The End” as appears in all his other works, so I’m betting there will be at least one more short or a partial feature that goes into production before Miyazaki-sensei departs this earthly realm. If it turns out to be his last, I consider myself extremely lucky to have shared this reality at the same time as this master storyteller.