Each October, the Unsung Horrors podcast does a month of themed movies. This year, they will once again be setting up a fundraiser to benefit Best Friends, which works to save the lives of cats and dogs across America, giving pets second chances and providing them with happy homes.

Today’s theme: Unsung Horrors Rule (under 1,000 views on Letterboxd)

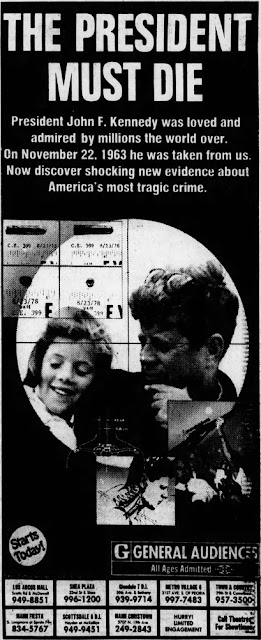

Urban legend says that it was tested in theaters in Arizona and Virginia in January 1981, but performed poorly. It was ultimately shelved and is now considered a piece of “lost media.” Just a few months later, the real-life assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan made it an impossible movie to market.

Or so they say.

I interviewed James Conway, this film’s director, for an upcoming issue of Drive-In Asylum and got to ask about this movie, one that has fascinated me for years:

DIA: One last question about that era. What happened with The President Must Die?

JAMES: It was sort of the end of our believing in the market research and testing of ideas. Because when we tested that – making some trailers – it received incredibly high ratings. Everybody wanted to see this movie. We made the movie and did an excellent job. I mean, it’s absolutely authentic based on the time. I flew all over the country, interviewing all these people who you’ll see in the movie, and when it opened, nobody cared. Nobody came to see it.

DIA: In my research, I’ve heard that it was pulled from theaters in the wake of Reagan being shot. Is that true?

JAMES: I know it didn’t perform. I’m not sure about the Reagan thing.

I’ll tell you a funny story. Though. We moved the company from LA to Park City, Utah when we did Grizzly Adams in 1976 and I moved there as well. I moved back to Los Angeles in 1982, but kept a home there. It’s where I live now, several months a year.

We did the post-production for The President Must Die in Park City and we’re flying with all the reels to go to LA to do the mixing and have all the boxes with all the reels. And in those days, I don’t know how old you are, but when you used to do sound effects and music, you’d have 30-40 reels for each movie. Each of these boxes had The President Must Die marked on them, ready to be sent on a United Airlines plane to the sound editors in LA.

Somebody who saw the boxes saying The President Must Die called the FBI, and the people who were flying to LA with those boxes were pulled off the plane as soon as they hit the ground. But once they explained what it was, they were let go. But isn’t that fun? (laughs)

At the end of the interview, as I was fact-checking a few things, I told him that this movie was one of my holy grails.

“Do you want to see it?” Conway asked. “Check your email.”

Imagine my joy at hearing the dulcet tones of Brad Crandall again, a voice I figured I’d heard everything from in all of the other Sunn films. Now, he’s setting up the story of JFK and how he was changing America. Unlike so many other conspiracy films, this begins and ends with positivity.

You also have to understand that in 1981, there weren’t many other, as I said, conspiracy films.

Conspiracy wasn’t what it is today. It was in photocopied sheets and by word of mouth. There was no internet. There were just pockets of this information, and you had to hunt for it. A relatively mainstream film espousing the idea that Kennedy was killed by one of the many groups it could have been (in fact, at one point, Crandall says, “Who would want to kill someone as popular as Kennedy?” and nearly answers himself by suddenly naming at least five groups that absolutely hated him and had a motive.

This movie shows the Zapruder film from a time when you couldn’t just look it up on your phone.

The only evidence, for years, that it even existed was a Bantam tie-tin paperback co-written by Sunn’s Charles E. Sellier, Jr.

But it’s real.

In the February 2-3 issue of Parade, an article, “Making Movies the Computer Way,” was published. In it, this film is discussed:

“Once the most popular ideas are collated, Sunn’s research teams are sent out again. This time, the man on the street is asked to help flesh out the concepts. Take, for example, the research conducted for The President Must Die, a docu-drama on the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

“After feeding our data into the computer,” explains screenwriter Brian Russell, “we went with the conspiracy theory – the premise that was closest to what the majority believed.” What if the computer had pinned the blame solely on Oswald? “We would have gone with that angle instead,” Russell says. “We’re interested in drama, not politics.”

(This appeared on Temple of Schlock.)

We all know the Magic Bullet Theory now, probably by heart. But to see a much younger Cyril Wecht discuss it in detail is incredible. What did people in 1981 even think? I mean, what did I think the multiple times I saw Wecht speak live, where he would gather four audience members, create the seating arrangements of Kennedy’s death car (which is now in Michigan).

This is from a time before when our own President espoused conspiracy theories and gave dog whistles to Q-Anon, using it when it benefited his cause and rapidly disposing of it. We’re to care and not care about conspiracy; today it feels as if it’s transitory and can come and go as easily as the wind. How did the ear grow back? Was the election fixed or wasn’t it? Is Project 2025 real or not? Everything is truth and fiction at the same time; feelings and emotions matter more than evidence.

Here is this documentary from a time past Watergate that recognizes that the innocence of the nation — one that had not yet discovered that the Third Reich studied Jim Crow laws as inspiration — was damaged by the deaths of JFK, RFK, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr., as well as both Nixon leaving the office and Ford nearly being assassinated twice, once by Manson Family member Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme and the second by a radicalized Sara Jane Moore. Crandall even wonders, aloud, if America can ever find hope again.

In the past, you were a kook for believing that the Warren Commission could lie to you (as an aside, I still hate the line in Bull Durham, “I believe Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone,” but then again, Kevin Costner was also Jim Garrison). You were more sane to believe in the Warren’s Single-Bullet Theory, one that argues that “a single bullet struck Kennedy in the back, exited his throat, and then wounded Governor Connally, who was seated in front of him.”

In James Shelby Downard’s “King-Kill/33: Masonic Symbolism in the Assassination of John F. Kennedy,” the conspiracy theorist (artist?) wrote, “Most Americans are beyond being tired; the revelations have benumbed them.”

Downard claimed, way back thirty years or more ago, “Never allow anyone the luxury of assuming that because the dead and deadening scenery of the American city-of-dreadful-night is so utterly devoid of mystery, so thoroughly flat-footed, sterile and infantile, so burdened with the illusory gloss of ‘baseball-hot dogs-apple-pie-and-Chevrolet’ that it is somehow outside the psycho-sexual domain.” I have lived by those words since I read them, as well as his belief that “Only the repetition of information presented in conjunction with knowledge of this mechanism of Making Manifest of All That is Hidden provides the sort of boldness and will which can demonstrate that we are aware of all the enemies, all the opponents, all the tricks and gadgetry, and yet we are still not dissuaded, that we work for the truth for the sake of the truth. Let the rest take upon themselves and their children the consequences of their actions.”

We work for the truth for the sake of the truth.

I may hide inside movies and explore the archaeology of what was lost, but I dream of what could be. This film reminds me of that.

This was an interesting movie to watch in the wake of several political and business-based killings this very year. Much like The Killing of America, the questions asked in this movie haven’t been answered. They probably never will be.

But I’ve solved one of my own conspiracies.

I’ve actually got to see this. Thanks, James.

You must be logged in to post a comment.